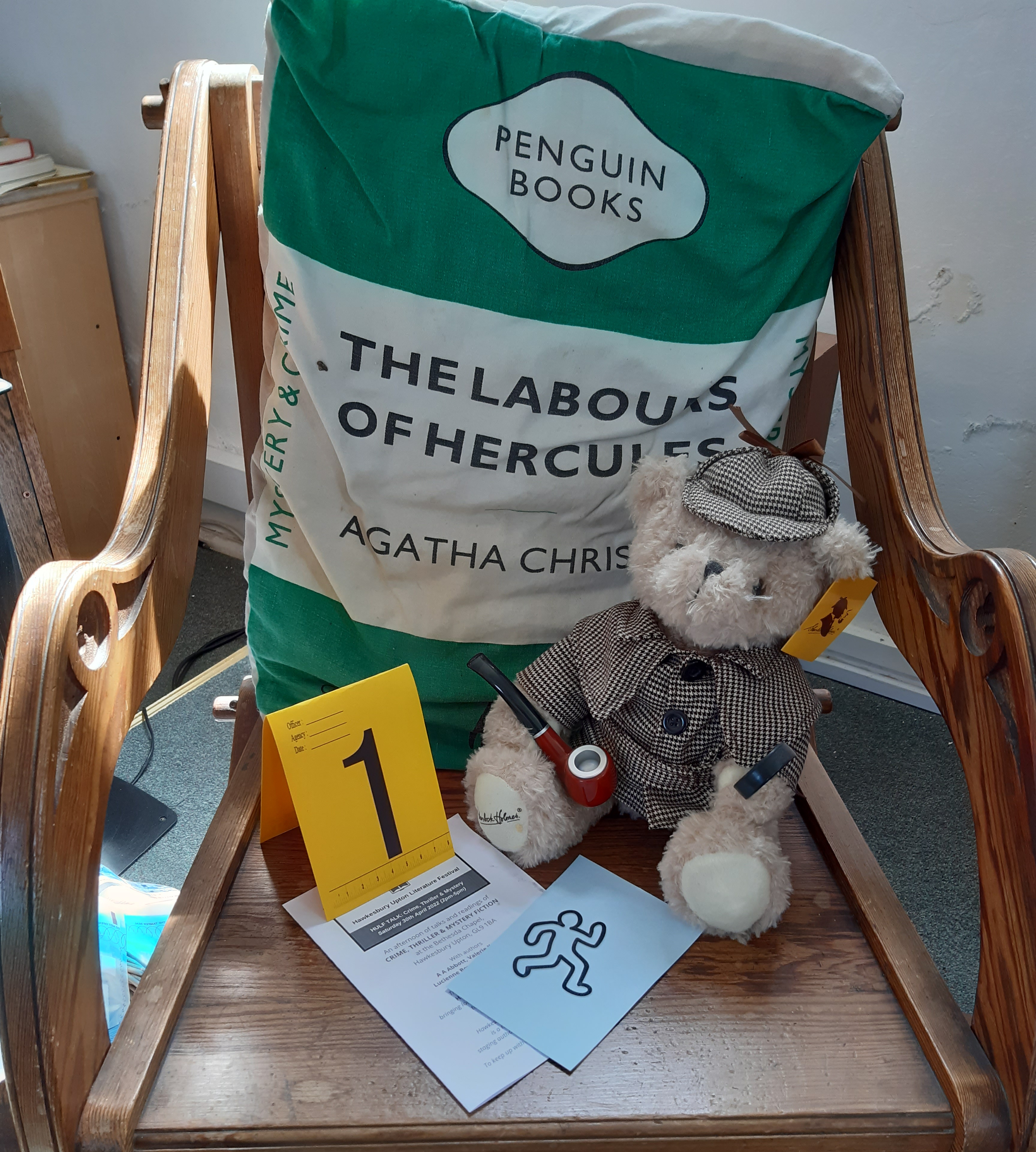

This is the talk I gave at the Hawkesbury Upton Literature Festival HULF Talk on 30th April 2022 on the topic of Crime, Thriller and Mystery Fiction. See www.hulitfest.com for more information about that talk and future HULF Talks.

My favourite period is crime-writing is the 1920s and 1930s. I’ve been reading books from the Golden Age of Detective Fiction since my teens, and it has also given me role models for my own writing.

Although many of its authors continued writing well after the Second World War, the term The Golden Age of Detective Fiction refers to the inter-war years, when society was still reeling from the impact of the First World War. Then in 1918, the Spanish Flu pandemic killed more people than the whole of the war. Tragically, unlike Covid, this was a strain of flu which particularly affected young people with strong immune systems – the generation that had been so decimated in the trenches. The authors writing in the Golden Age of Detective Fiction had seen horror indeed, which influenced and informed their writing lifelong.

Famously Agatha Christie’s intimate knowledge of poisons was gained from her voluntary work as a nurse, then as an apothecary’s assistant in a hospital for those sent home wounded from the First World War battlefields. Hercule Poirot was inspired by seeing Belgian refugees sent to her hometown of Torquay.

In Dorothy L Sayers’ early novels, her sleuth Lord Peter Wimsey has frequent flashbacks to the war. He suffers shell shock at times of crisis, (in an era when shell shock was only starting to be acknowledged and understood), from which he is rescued by his faithful manservant Bunter – the same batman who had saved his life during the First World War, rescuing him from a shelled dug-out in the trenches.

Perhaps one reason handguns seem to proliferate in these stories is that so many men seemed to hang on to their old service revolvers. There always seems to be one handy in the desk drawer of the country house study or wherever else the writer needs to find one for the murder of a victim or the suicide of a rumbled killer seeking to avoid the gallows.

That’s another dark feature of the detective fiction of this era. Although not all the stories are of murder, most of them involve the inevitable sentencing of convicted murderers to the death sentence by hanging – capital punishment was not abolished until 1953.

So although the phrase “Golden Age” suggests nostalgia for an idyll, it arose from a dark place. It was also in some respects pioneering and forward-looking, bringing to the public’s attention what were then ground–breaking and modern themes. The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club mentions the influence of “glands” on behaviour, which had just been discovered. Also forensic pathology and the psychology of serial killers, before the term serial killers had been coined. For this reason, Sigmund Freud was a fan of Golden Age Detective Fiction.

But just like everyone else, the detective writers sought respite from tragedy in fun and frivolity. They wrote to the sounds of the Jazz Age with its freer, impulsive music. They wore less fettered fashions than before the Great War, allowing them freedom of movement. They embraced the motor car to give their heroes and villains independence and mobility – Dorothy L Sayers even rode a motorbike herself – even if they did seem to drive them off the road and into ditches with alarming frequency. Well, there was no “health and safety” in those days, and no law against drink-driving. Drinking alcohol around the clock was no deterrent to getting behind the wheel, and whisky and soda was a standard nightcap.

Of course, the detectives back then did not have the advantage of modern technology – no internet, no satellite tracking, no mobile phones – but it was a case of swings and roundabouts. With terrestrial telephony still in its infancy, they could arrange for any suspicious call to be traced at the exchange, because calls were still connected manually by human beings. In one mystery (I think a Margery Allingham Albert Campion novel?), the sleuth is able to trace a particular car in the middle of London because it is remembered by a traffic policeman on point duty.

Although many popular Golden Age novels feature privileged people in Wodehousian settings, the authors came from various backgrounds, from the working class to the aristocracy and across the full political spectrum from hard left to far right. Many were free and original thinkers, defying the social conventions of their day. Some had difficult personal problems – Sayers secretly gave birth to a son and had him adopted by a cousin without even her parents or her employers knowing, and we may never know the truth behind Christie’s infamous eleven-day disappearance in 1926. Such secrets would be nigh impossible to hide in the 21st century and the age of the paparazzi.

What united this assorted bunch of authors was their approach to the detective story as an intellectual puzzle – almost like a parlour game, or that new and highly popular fad, the crossword puzzle, invented in 1913.

They imposed upon themselves a strict code of fair play, to give the observant reader a chance of solving the mystery alongside or even before the sleuth in the story. Wimsey’s mother likes his love interest, Harriet Vane, a detective writer, because it takes her longer than usual to guess the villain.

One of their number, Ronald Knox, whose day job was that of a Catholic priest, came up with ten commandments of detective fiction, which I’ll read you now:

- The criminal must be someone mentioned in the early part of the story, but must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to follow.

- All supernatural or preternatural agencies are ruled out as a matter of course.

- Not more than one secret room or passage is allowable.

- No hitherto undiscovered poisons may be used, nor any appliance which will need a long scientific explanation at the end.

- No Chinaman must figure in the story.

- No accident must ever help the detective, nor must he ever have an unaccountable intuition which proves to be right.

- The detective must not himself commit the crime.

- The detective must not light on any clues which are not instantly produced for the inspection of the reader.

- The stupid friend of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal any thoughts which pass through his mind; his intelligence must be slightly, but very slightly, below that of the average reader.

- Twin brothers, and doubles generally, must not appear unless we have been duly prepared for them.

Although there are plenty of writers who break these rules and still come up with great tales – I’m sure there are plenty of Chinamen in Sherlock Holmes, for example – and the tone of these commandments is tongue-in-cheek, I reckon for the most part they’re a good rule of thumb even now.

The authors concurred and colluded in other ways. Nowhere is this clearer than in the formation of the Detection Club, founded with 26 author members, including some who are still household names – Agatha Christie, G K Chesterton, Dorothy L Sayers – as well as many who though hugely popular in their time went out of fashion until revived by the British Library Crime Classics series a few years ago. Its membership included writers better remembered now for other kinds of fiction – Baroness Orczy of Scarlet Pimpernel fame, and Christiana Brand of the children’s Nurse Matilda series, and even A A Milne.

This was a private club which met regularly to talk shop, and they had a formal constitution and rules, including a guarantee of quality. To qualify, members generally had to write at least two novels of a certain literary standard (although they happily admitted A A Milne, who wrote just one, because – well, Winnie-the-Pooh!), and in which detection had to be the main interest.

Its current president is Martin Edwards, and he is also officially the Club’s archivist. If you’d like to know more about the extraordinary lives of the Club’s first members, I highly recommend his account, The Golden Age of Murder.

If you prefer to discover them through the pages of fiction, there’s a unique way to sample twelve of them in a single book, a novel, The Floating Admiral, a remarkable collaboration. Each of the twelve authors wrote a chapter, without conferring with the others on the plot or the eventual outcome, adding more red herrings and twists as they went along, until Anthony Berkeley had the unenviable task of pulling them all together in the final chapter, which he entitled, “Clearing Up the Mess”. A fascinating appendix presents how each of the contributors would have solved the mystery, and their solutions and interpretations of the previous chapters to theirs are completely different.

The Detection Club is still going strong, although its reach has broadened. As Simon Brett, its president from 2000-2015, says, “Crime fiction is a much broader church now that it was in the 1920s and 1930s”. Which leads us neatly into our discussion of the thriller, with Valerie Keogh and A A Abbott…

To read Lucienne Boyce’s talk about The Victorian Origins of Crime Writing, you can now do so on her blog here:

https://francesca-scriblerus.blogspot.com/2022/05/the-victorian-origins-of-crime-writing.html

It has great illustrations too!

See www.hulitfest.com for more information about future HULF Talks.

You have talked on my favourite period of detective novels, many thanks

I’m so glad, Margot! Lovely to hear from you.